Latinas Do It Better—4 Women on the Cultural Importance of Their Bikinis

For teenage girls living in Brazil, a coming-of-age fashion moment wasn’t buying a pair of fuzzy Ugg boots or a Juicy Couture tracksuit—it was getting a barely there string bikini. Thirty-year-old Bianca de Oliveira remembers her first one well; her mother bought her a fio dentário—aka a dental floss style bikini—when she was 13 years old. As the name suggests, not much was left up to the imagination.

“You’re becoming a teenager, and your body is changing. You want to feel like a grown-up,” De Oliveira explains. To her and most Rio natives, skipping the beach on Sundays was sacrilege. Every weekend, De Oliveira and her friends would head down to Copacabana to soak in the sun. For the most part, it didn’t matter what your body looked like, she says. Everyone—old and young, chiseled or not—had qualms about showing off their bodies. “Sexuality isn’t the right word. … We’re just open with our bodies, and that’s why bikinis keep on getting smaller. Growing up, I thought it was weird when I was wearing a [one-piece] bathing suit. It felt unnatural.”

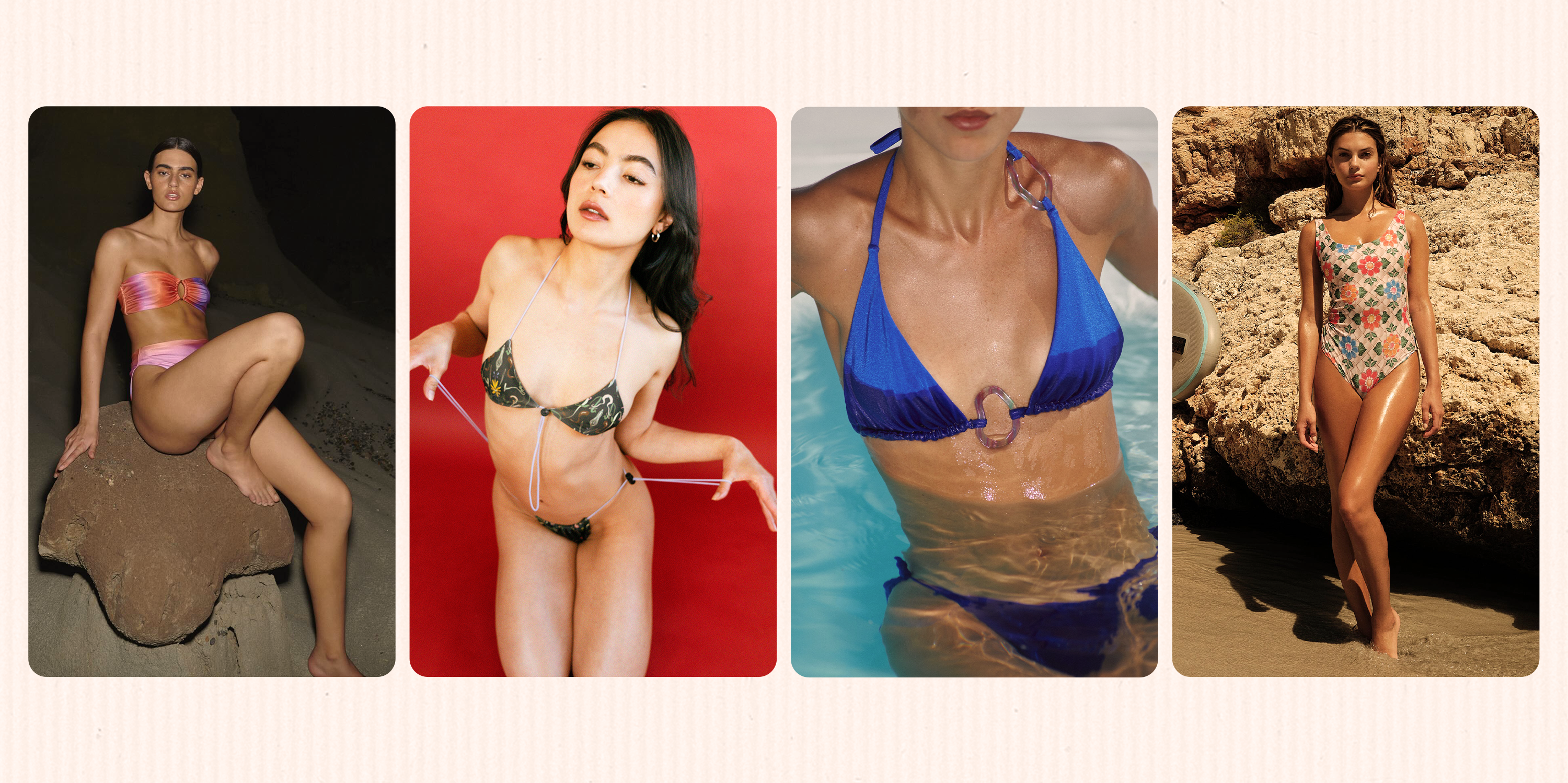

While the beaches of Copacabana and Ipanema have cemented themselves as beachwear capitals thanks to their teeny-tiny bikinis, as a whole, the Latin American swimsuit industry has always been lauded as a pioneer in the space thanks to its attention to detail, artisanal production, and most importantly, focus on flattering fits. Although it might seem outrageous to spend more than $20 on a triangle string bikini in our fast-paced, hyper-capitalist world, Latina women across the diaspora know that their pieces aren’t just for a sultry cabana-side thirst-trap selfie—they’re for life.

While modern bikinis, first created in 1946 by French fashion designers Jacques Heim and Louis Réard, took off in the '50s and ’60s, the low-cut, thong-esque style favored by Latin beachgoers wasn’t made popular until the mid-’70s. As the decades progressed, so did the amount of skin showing. By the ’90s and early 2000s, barely there bikinis were the go-to choice for women living in South America, the Caribbean, and Miami.

InStyle fashion editor Frances Solá-Santiago’s life was filled with scantily clad women in bikinis—first on the beaches of Puerto Rico (which she calls home), and later, on telenovelas and the Miss Universe pageant reruns where she’d watch Zuleyka Rivera win the 2006 crown.

“In Puerto Rico, the one-piece is not really a thing. It was bikini or die,” Solá-Santiago explains. Her first memory of buying a bikini was at nine years old when she was on holiday in the neighboring Dominican Republic. The one-piece swimsuit, she explains, was only reserved for grandmothers or conservative types going to the beach—everyone else was in a flattering, body-enhancing swimsuit. While there was a normalization that came along with seeing everyone in a two-piece set, that doesn’t mean there wasn’t a pervasive, undercurrent of body standards determining who looked good in their bikinis.

“In our daily lives, there’s a lot of crude conversations happening at the beach about men and what bodies they prefer,” she explains. The “voluptuous,” Latina woman stereotype comes to mind: a large bust and behind, a toned, flat stomach, wide hips, and sculpted arms. In return, most swimwear would prioritize enhancing certain aspects of their swimsuits by offering thick, double-lined Lycra material that creates a tight, smoothing effect similar to Spanx and an adjustable string construction to ensure that the bikini top will fit different bust sizes. At the end of the day, Solá-Santiago points out, most of our beloved bikini brands and silhouettes prioritize sex appeal above all. It’s a strange relationship that still exists for her. “To be quite honest, I’m not the type of person that buys a lot of swimwear, and I think it’s because of that I wasn’t very comfortable shopping for swimwear at all,” she explains. “I couldn’t ever see an emphasis on comfort or feeling okay in whatever bikini you were wearing. It was always more like, ‘This is what’s going to make you look hot.’”

Latin American swimwear is known for being ultra-flattering—whether you believe it yourself or whether it’s via the comments you’ll get from strangers on the beach, asking where you got your swimsuit from. Manuela Uscher, a 25-year-old Colombian-born fashion publicist who grew up in Miami, would always offhandedly say they were from Colombia to anyone who asked. (She assures me that she wasn’t trying to gatekeep.)

Each year, Uscher’s cousin back home in Medellín, Colombia, sends mirror selfies wearing bikinis to Uscher, who saves the ones she wants to buy and sends payment. “It’s like smuggling contraband,” Usher jokes, noting the conversion rates significantly favor buying pieces overseas. Brands from Colombia’s northern coast like Maaji, Almamia, Baobab, Agua Bendita, and OndadeMar are her favorites. “There’s a different point-of-view compared to what the American consumer wants it feels more fresh and there’s much more variety.”

Swimwear brands from Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico are masters of their craft, and they often come at a hefty price (a single bikini set may cost you upwards of $200 if you’re buying from outside of the United States). But for those living across the diaspora, they’re well worth the cost. “So many American bikini brands are quite boring—they’re a one-color, push-up-style bikini for $180. I’m not spending that kind of money for flimsy fabric and a style that doesn’t do anything for me,” says Uscher. “If I can buy a Colombian bikini for $80 that’ll last me five years minimum, why wouldn’t I do that?”

While Brazil and Colombia dominate the luxury swimwear and resort-wear space, there are still hundreds, if not thousands, of designers who are challenging what Latin-made swim is to them. Designer Valeria De La Fuente created her eponymous label, Valeria Anastasia, 10 years ago this month. After competing on Project Runway: Latino America, a friend asked her to make a swimwear collection to sell at one of his boutique hotels. Her brand, which originates from Monterrey, Mexico, focuses on ethical production and a comfort-first design, bridging the gap between ready-to-wear and traditional resort wear. At the end of the day, the core tenets are the same between her brand and the brands that have become million-dollar swimwear empires: fit, above all, has to be perfect. For De La Fuente, though, her pieces are designed from a woman’s perspective and not from a societal view of what’s considered “sexy.”

“It was always about functionality and comfort above all else. I wanted pieces that I could wear all year long,” she explains. During our Zoom call, she’s wearing one of the brand’s Amber pieces that looks more akin to a going-out top than the top half of a bikini set. “Where I’m from, people are still pretty conservative about swimwear, but I still want everyone to feel hot and sexy, but in their own way.”

De La Fuente has lived in New York for two years, aiming to bridge the gap between what her Mexican consumers want and those from the United States. While her Mexican consumer is attached to the brand’s colorful prints and geometric shapes (a staple within the Latin American swimwear market), her small, but growing, New York clientele is drawn to the understated, chic minimalist pieces the brand offers. Like other Latin swimwear brands, Valeria Anastasia produces most of its suits by hand, hand-cutting and designing most pieces with a skilled atelier of local craftspeople. Not only do things look good, but they actually have to be good. In the past, her designs have been stolen by mass-production wholesalers on AliExpress or Amazon, which offer a similar bikini for less than $30. To her, it’s disheartening, but further proves the point she keeps on coming back to during our conversation, time and time again: “Just like Bad Bunny said, ‘Everyone now wants to be Latino.’”

“I think what makes the Latin swimwear market so attractive is that when you see Latin people at the beach and you see these women wearing these beautifully constructed bikinis, they exude confidence,” De La Fuente explains. “The inner work of feeling comfortable with our own bodies and feeling sexy enough to wear what we want is so alluring and attractive to people who aren’t from our cultures.”

Naturally, there’s still a ton of work to be done. De Oliveira, who lives in currently Sweden, says she’s able to find cute, attractive bikinis for plus-size women like herself (although, she jokes, don’t ask her to wear a European-cut bottom instead of her Brazilian thongs since it’s akin to “a diaper”). Miami Swim Week, which focuses on bringing Latin American swimwear and resort-wear brands stateside has never been more popular. Solá-Santiago, however, notes that during a recent trip, she had conflicting feelings about the types of beauty standards brands were promoting via their casting decisions. "It might not be the healthiest thing to be seeing while growing up," she says, given the fact that there’s often only one type of body type being promoted during most of the runway shows and presentations.

“I think to really admire how good our brands are (with resort wear and swimwear being such a big strength of Latin American and Caribbean designers), we have to expand the range of bodies that those brands are shown on,” Solá-Santiago explains. “The minute we do that and make everyone comfortable with accepting swimwear as second skin, I wouldn’t be surprised to see even more interest in the market.”

Ana Escalante is an award-winning journalist and Gen Z editor known for her sharp takes on fashion and culture. She’s covered everything from Copenhagen Fashion Week to Roe v. Wade protests as the Editorial Assistant at Glamour after earning her journalism degree at the University of Florida in 2021. At Who What Wear, Ana mixes wit with unapologetic commentary in long-form fashion and beauty content, creating pieces that resonate with a digital-first generation. If it’s smart, snarky, and unexpected, chances are her name’s on it.